The Capital Region consists of three major funding jurisdictions, along with dozens of public and private transportation operators. The region cannot achieve an optimized transportation system without tackling the core issues around how the transportation system is governed and funded.

Under current projections, roadway congestion will worsen across the Capital Region through 2040—increasing by more than 150 percent from 2015 levels.1 In other words, by 2040 the region’s consumers will go from sitting in congestion 30 percent of each trip to nearly 50 percent.2 With nearly 50 percent of the region’s residents crossing county borders and 20 percent crossing state lines to access their job sites,3 the region’s governing entities must be able to both plan for and invest in the region’s transportation system to match the region’s growth.

To change the current trajectory, each Capital Region jurisdiction should actively engage in reforming the way the region governs and pays for transportation.

Capital Region Performance

The region’s institutions and transportation investments must be examined to ensure they are making the best use of each transportation dollar. Businesses justify their spending to shareholders by clearly outlining the data-driven expected benefit, rate of return, or strategic imperative for each investment, and measuring if these outcomes are achieved over time. This level of transparent, objective decision making and accountability should be expected for the multibillion-dollar annual transportation investments in capital and operating budgets from the region’s transportation agencies.

Yet, often, it is unclear how transportation investments achieve stated goals or outcomes for the transportation system or for the region. Transportation agencies and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) often present projects to the public without comparing one investment against others—leaving the decision making process for transportation investments a mystery to both the general public and many professionals in the transportation community. This is often due to the fact that politics sometimes overrides smart, data-driven analysis for transportation decision making. The result can be transportation investment decisions that siphon resources away from more worthy initiatives and, ultimately fail to address the region’s needs.

Unfortunately, consumer access to opportunity is not typically used as a key input in determining and evaluating transportation investments and performance. In the Capital Region, access to opportunity varies widely based on an individual’s income and race, and that inequity only holds back our region’s growth. The Partnership encourages the Capital Region’s transportation agencies to incorporate a common definition of equitable access, and proposes the use of the following:

We define equitable access as every resident of the Capital Region—regardless of the person’s community, race, ability, or background—having consistent, safe, affordable, and dependable physical access to quality employment with living wages and benefits, education, and necessities that enable economic mobility and opportunity.

In adopting this definition, Maryland, Virginia, and the District—alongside their MPOs, transit agencies, and local governments—should move beyond mitigating negative impacts to low-income and majority-minority communities from transportation decisions. The region can overcome this challenge by intentionally making equitable access a key factor in its performance-based plans and investments to measurably improve access in communities with lower levels of mobility.

In particular, Baltimore’s public transportation system’s governance and funding structure must be adjusted to improve accountability from all parties. The metro area’s public transportation system is one of just a few in the country that is governed and operated by a state agency rather than a regional authority or local transportation department. Funding for public transportation in Baltimore reflects this governance structure: The primary source of funding for Maryland Transit Administration (MTA) capital and operating expenses is the state Transportation Trust Fund. The city and counties do not contribute to MTA’s services. Under this structure, Baltimore’s public transportation system has not kept pace with repair and service needs or developed a strategy to enhance existing service. This governance and funding structure must be reformed to enhance accountability from all vested stakeholders and shared investments to create a globally competitive rapid and reliable transit system in the Baltimore metro area.

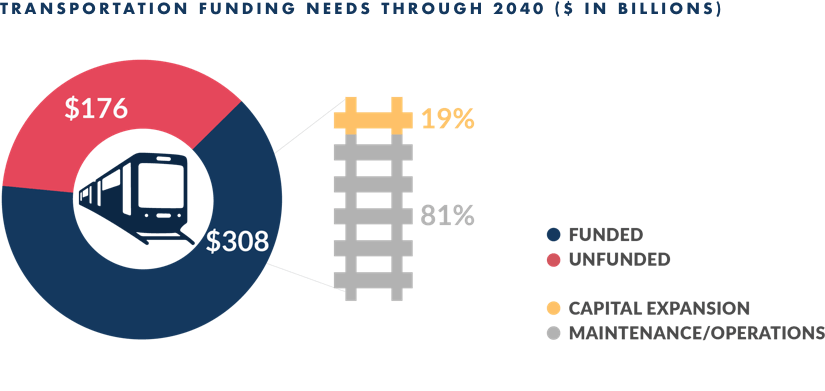

While our region can do much more with current resources, additional funding will be needed to fully transform the region’s mobility outcomes. Although Maryland, the District, and Virginia have each passed transportation funding bills since 2013 that are projected to increase transportation revenues by more $7 billion by 2019, the Capital Region lacks $176 billion needed to address identified capital, operations, and maintenance improvements through 2040 (approximately 36 percent above expected funding levels).4

Strengthening federal resources in Capital Region transportation projects will help close this funding gap by speeding up delivery of critical transportation investments and will also benefit both our local communities and our national economy. Federal support for the Virginia Atlantic Gateway multimodal I-95 corridor congestion relief program is projected to provide nearly $3.5 billion in economic benefits—leveraging federal, state, and private investments more than 3:1—and improve the highway and rail corridors that move over 350 million tons of freight each year and more than 400,000 people a day.5

To speed up these types of investments, the United States Congress must increase federal funding—starting with the first federal gas tax increase in a quarter century. Taxes on gasoline serve as the primary source of funding for transportation investments at all levels of government. Yet gas tax revenues are not keeping pace with current or projected transportation funding needs. The federal gas tax remains stuck at 1993 levels, which has eroded its purchasing power by more than 40 percent over the past quarter century.6 With inflation and rising costs, Congress must pull from elsewhere in the federal budget to mask the shortfalls in the nation’s transportation fund—just to maintain status-quo funding levels.

In addition, the region can be more effective in partnering to increase our rate of return from existing competitive grant programs to fund critical investments. As the number of low- or no-gas vehicles on the road increases, the resulting decrease in gas tax revenues is expected to grow the Capital Region’s transportation funding gap an additional $42 billion by 2040—to more than $200 billion.7 As a result, the region needs to begin planning for the future and begin to identify viable alternatives to gasoline taxes. The region can begin piloting innovative funding sources now in Maryland, Virginia, and the District, in partnership with the U.S. government.

Actions

Citations:

- UMD analysis of the Chesapeake Bay Megaregion Model.

- Ibid.

- Each day, 49 percent of all commuters—2.4 million people—in the Capital Region cross county lines to get to their place of work. Seventeen percent of the region’s commuters travel across state borders to access jobs. Partnership analysis of U.S. Census American Community Survey.

- Partnership analysis of the 2040 long-range transportation plans for the BRTB, TPB, FAMPO and RRTPO.

- Atlantic Gateway: Partnering to Unlock the I-95 Corridor. VDOT and DRPT FASTLANE Grant Application prepared for USDOT, April 14, 2016. http://www.virginiadot.org/projects/resources/atlantic_gateway/Atlantic_Gateway_FASTLANEGrantApp2016.pdf.

- “More Stop-and-Go Financing of Highway Trust Fund.” Peter G. Peterson Foundation, May 2015. https://www.pgpf.org/budget-basics/more-stop-and-go-financing-of-highway-trust-fund

- Partnership analysis of Federal Highway Administration Traffic Volume Trends and Motor Fuel and Highway Trust Fund, and U.S. Energy and Information Administration Annual Energy Outlook and U.S. Total Gasoline Wholesale/Resale Price by Refiners.

- “Metro gets third and final ‘yes’ as Maryland commits to its full share of dedicated funding.” The Washington Post, March 22, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/trafficandcommuting/metro-gets-3rd-and-final-yes-as-maryland-commits-to-its-full-share-of-dedicated-funding/2018/03/22/ecd63946-2dfa-11e8-8ad6-fbc50284fce8_story.html?utm_term=.b5e4ca1dedcf

- “Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority: Assessing Fiscal Risks and Improving Workforce Management Would Help Achieve Strategic Goals.” United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters, September 2018. https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694418.pdf

- “Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority: 2017 Annual Agency Profile.” National Transit Database, 2017. https://www.transit.dot.gov/sites/fta.dot.gov/files/transit_agency_profile_doc/2017/30030.pdf

- “Public Hearing on Bill 22-568, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Dedicated Funding Act of 2017.” Testimony of Jeffrey S. DeWitt, CFO, Government of the District of Columbia, February 7, 2018. https://cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/release_content/attachments/DeWitt%20Testimony%20-%20WMATA%20020718.pdf