Action 1.2

Create a Redevelopment Compact to Expand and Modernize Union Station; Redevelop Baltimore Penn Station and Staples Mill Station

What

Union Station must be significantly expanded and modernized in order to meet growing demand and keep the region globally competitive. Once the federal environmental planning process is complete, the modernization project—including a new train shed with three separate concourses, new platforms, new levels for trains and commerce, and significantly better transit and bus access—can begin. This will lead to increased capacity, a better consumer experience, and enhanced vitality for the region’s economy. This project will be transformational and will create a world-class multimodal transportation hub as well as a new neighborhood.

Baltimore Penn Station opened in 1911 and is the eighth busiest train station in the country—serving nearly three million Amtrak intercity and Maryland Area Regional Commuter (MARC) commuter passengers each year.1 Amtrak—the owner—has secured a master developer to rehabilitate the station and redevelop surrounding properties to create a world-class multimodal station that serves as a central gateway for travel and commerce in Baltimore.

Staples Mill Station has changed little since it was opened in 1975, when it was designed for three round-trip trains per day. Today, the station sees 18 round-trip trains per day.2 Current and forecasted ridership far exceeds the original intended capacity—serving more than 1.5 million passengers annually, representing the busiest station in the Southeast.3 In 2018, Virginia’s Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) improved the station’s parking facility and doubled its capacity. This station is also owned by Amtrak, which is working with DRPT and Henrico County to advance efforts to plan for a redeveloped, mixed-use station.

Both Baltimore Penn Station and Staples Mill Station redevelopment projects are less complex than Union Station but deserve equal attention and effort to transform them into thriving mixed-use station developments able to spur demand for intercity and commuter rail service and reduce congestion on the roadway network.

Why

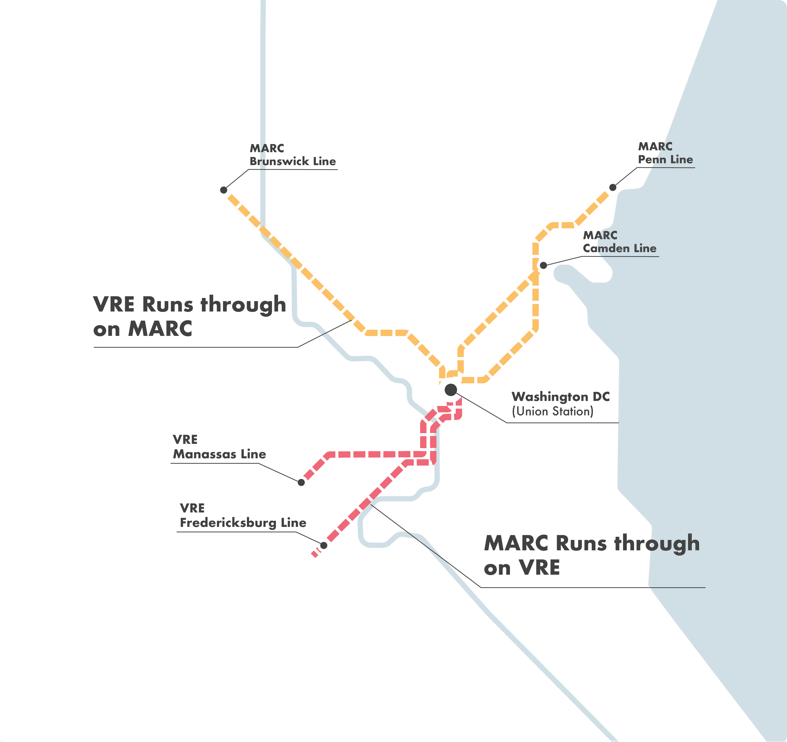

Located within a small footprint in a rapidly redeveloping community, Union Station connects nearly all surface public transportation services; attracts private mobility services like rideshare, tourist buses, and bike and scooter share; and serves as the front door for millions of tourists visiting the U.S. capital annually. A project of this magnitude will require sustained, accountable, and invested leadership from numerous key stakeholders over the next 15 years to fully realize the vision set out in the world-class 2012 Union Station Master Plan, including the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) (the owner of the facility), Union Station Redevelopment Corporation (USRC), Amtrak, Maryland DOT (MDOT), District DOT (DDOT), Virginia DOT (VDOT), Virginia Railway Express (VRE), MARC, Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), intercity bus operators, and Akridge (the master developer for the air rights above the tracks to the north of the station), among others.

Many elected officials and transportation agencies are supportive of the project overall, but none have stepped forward to propel the project from its current place in the early stages of the federal environmental planning processes and ensure its success moving forward. Without supportive elected leaders championing this project and in light of competing priorities from key stake holders, the federal environmental review process has slipped by more than two years. Funding commitments will be required by all key stakeholders, but no government or transportation agency has yet had to commit to significant cash investments, which will be needed to complete the $7.5 billion investment.4

The federal environmental planning process for Union Station is expected to be completed in early 2020, at which time the key stakeholders will need to secure funding commitments from all parties to complete construction within 15 years. Without a clear champion for the redevelopment of Union Station—and with many stakeholders—a contractually-binding redevelopment compact should be agreed to by all key stakeholders to identify each entity’s role in the project, investment commitments, and revenue sharing to efficiently sustain and deliver the transformative project.

Both Baltimore Penn Station and Staples Mill Station are thriving transportation hubs for their regions, but both are at capacity and require rehabilitation and expansion to meet existing and future demand. Penn Station is undergoing a planning process by a master developer, in coordination with Amtrak, to identify projects to maintain and expand the station terminal for train passengers, and enhance more commercial and residential development at the station and adjacent Amtrak-owned properties. Staples Mill Station must identify a strategy to expand capacity of the station and tracks while also leveraging these rail assets to induce economic development at the station and surrounding parking lot. At the same time, the state, CSX, and regional elected officials should advance efforts to run all trains through to Main Street Station in Richmond’s central business district, as recommended in the DC2RVA passenger rail plan. For each region to unleash the economic potential of having leading train stations, they must each invest in their stations and their connections to catalyze growth in ridership and development surrounding the stations.

Benefits

Redevelopment of train stations can drive economic development and increase train ridership. A redevelopment compact was expertly used to deliver Denver’s historic Union Station, a 1914 Beaux Arts building. The building is owned by the regional transit agency, which, along with the City and County of Denver, created the Denver Union Station Project Authority (DUSPA)—a nonprofit, public benefit corporation formed by the City of Denver to finance and implement the project. With participation from the state DOT and regional metropolitan planning organization (MPO), DUSPA was able to efficiently redevelop 50 acres of land surrounding the train station into a 21st century transit hub.5 The project cost nearly $500 million and included a hall for commuter and Amtrak passengers, a 22-bay regional bus facility, and light rail connections.6 The public entities contracted with a master developer to transform the train station into a mixed-use development. DUSPA established a special taxing district to repay loans secured from state and federal sources. The first phase of the project was delivered in 2014, has already generated nearly $4 billion in total economic impact in the near term, and is estimated to generate another $3 billion over the long term.7

Barriers

All three stations will have to secure significant funding to redevelop each station and its surrounding land, which may prove challenging. However, unlike Baltimore Penn Station and Staples Mill Station, Union Station is a complex project—and USDOT’s ownership of the station presents a significant barrier. Other comparable station redevelopments (e.g., Denver Union Station) have vested owners that possess the vision and regulatory flexibility to incorporate all transport modes and development considerations, and have it within their mission to primarily enhance their region’s economic and societal benefits. While a significant and sustained capital investment is needed to complete this project, a federally authorized redevelopment compact will help overcome challenges from Union Station’s unique ownership structure, larger size, construction period, and the complexity of the project.

Next moves

The expansion and modernization of Union Station, Baltimore Penn Station, and Staples Mill Station would not just elevate their immediate surroundings but help improve the entire region. Union Station is a complex project that warrants a redevelopment compact to ensure it is delivered within the next 15 years.

Next moves are:

- Amtrak, VRE, MARC, WMATA, and the private developer should agree to recommendations for a federally authorized redevelopment compact

- Baltimore Penn Station’s master developer, Penn Station Partners, should coordinate with public stakeholders to complete a visionary station development plan and move to construct projects starting in 2020

- Amtrak, DRPT, and Henrico County should complete a Staples Mill Station redevelopment plan and secure funding to redevelop the station building to accommodate existing and future passenger growth

Costs

While costs to redevelop Union Station exceed $7 billion,8 the recommended actions to create the redevelopment compact could be implemented with far lower investments from each stakeholder. Total costs to redevelop Baltimore Penn Station and Staples Mill Station are not yet available, but the planning can be completed for a minimal amount.

Expand to learn more

Collapse