Action 2.3

Complete the Baltimore Greenway Trails Network and Capital Trails Network, and Establish a Richmond Trail Network Strategy

What

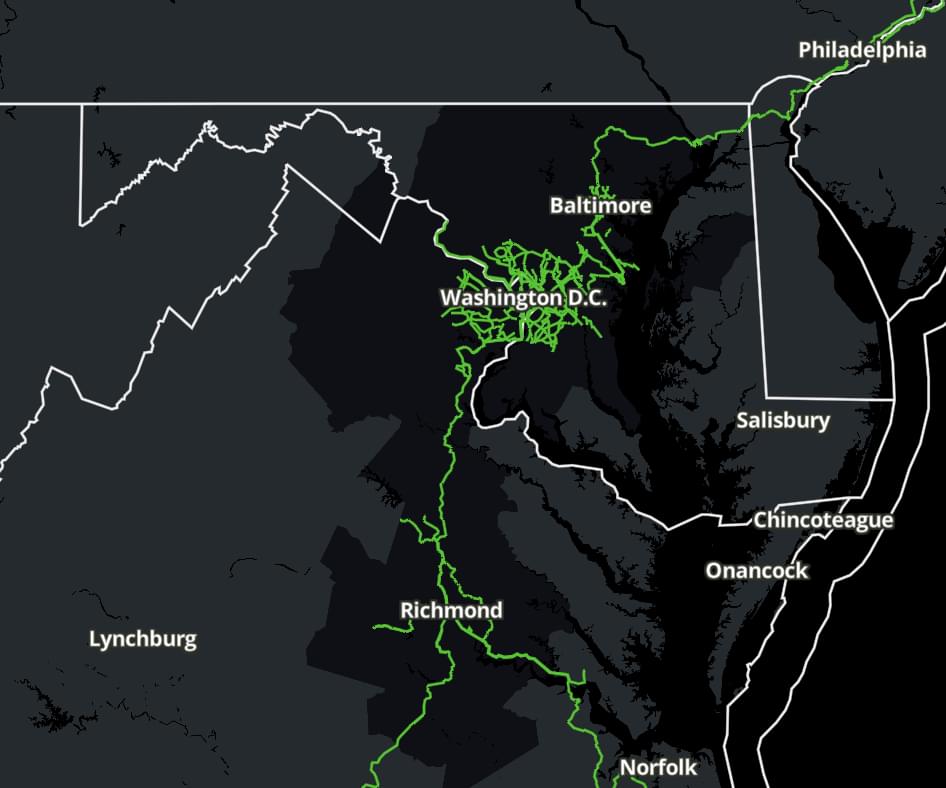

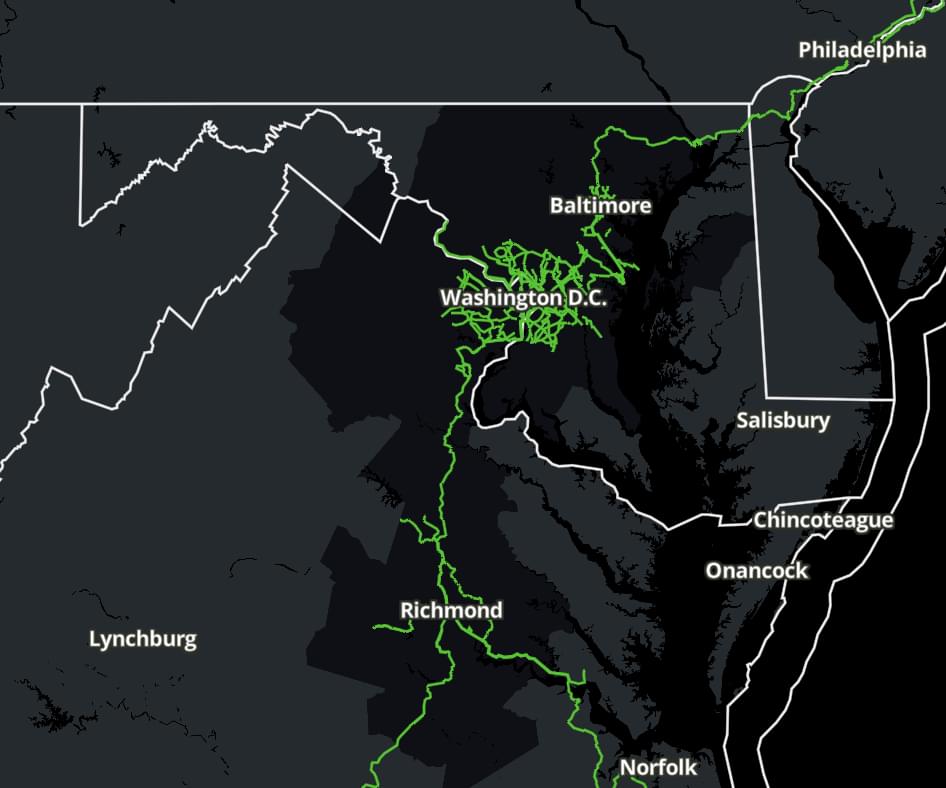

Connected trail systems can lessen demand on the roadway network, improve connections to jobs and activity centers, increase regional economic activity, contribute to healthy communities, and enhance access to the outdoors and our iconic parks and landscapes in both rural and urban areas. Maryland, the District, and Virginia have more than 1,000 multi-use trail miles, with major nationally-recognized trails such as the East Coast Greenway, the C&O Canal Towpath, the Anacostia Tributary Trails, the Capital Crescent Trail, the Mount Vernon Trail, the W&OD Trail, and the Virginia Capital Trail.

Yet, despite considerable investments, the region’s trails do not form coherent and connected regional networks in the Baltimore, Washington, and Richmond metro areas. In many instances, the trails also do not provide seamless connections to non-trail bicycle and pedestrian networks. Federal, state, and local governments should collaborate with trails groups and private entities to speed up the delivery of the Baltimore Greenway and the Capital Trails Network, and establish a trail connecting activity centers from Ashland to Richmond to Petersburg with the 52-mile Virginia Capital Trail.

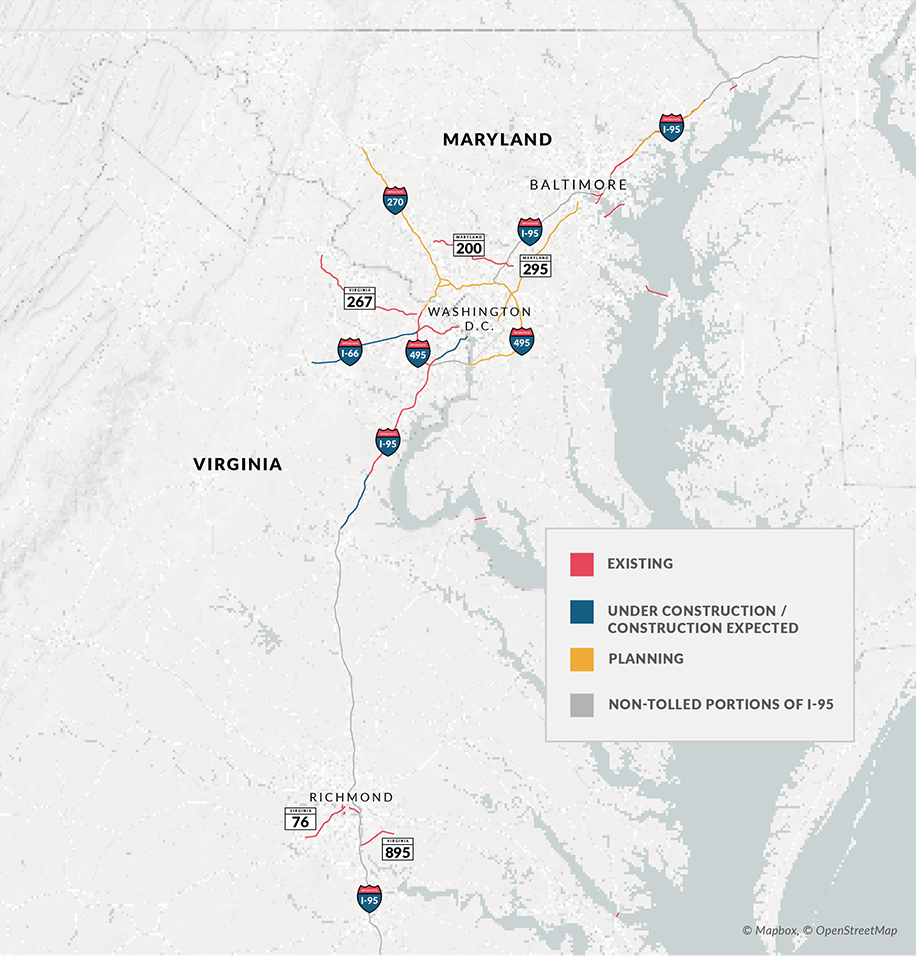

Capital Region Trails

Why

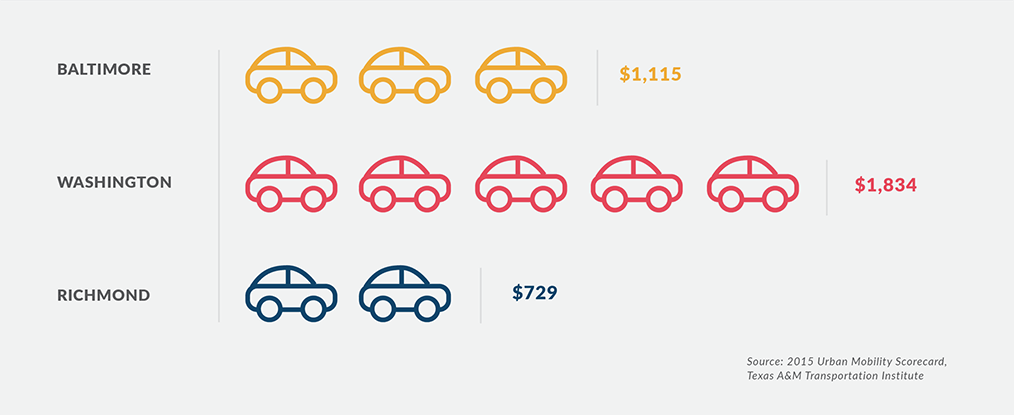

Many commute trips are less than five miles, a distance most can bike. In addition, many non-commuting trips can be completed efficiently by biking or walking if safe options exist. Trail connections to essential destinations such as jobs and transit stops can lower demand on the region’s roadway network, which reduces congestion.

However, the lack of trail connectivity diminishes the region’s ability to conveniently overcome man-made barriers, such as roads, to access jobs, schools, and outdoor opportunities. This lack of trail connectivity encourages consumers to drive rather than complete trips by bike or foot, limits greenspace for recreation, and isolates communities.

The Capital Region already benefits from clusters of locally and regionally connected trails in some areas. A few critical investments would create a network of trails—creating a sum far greater than its parts.

Baltimore City has more than 25 miles of existing trails. However, 10 miles of new trail in four key corridor gaps will connect the 35-mile Baltimore Greenway Trails network.1 The planned network will better connect more than 60 diverse neighborhoods—many of which are isolated from upward social and economic mobility opportunities due to limited transportation connections, whether by vehicle, transit, bike, or walking.2 This network will also connect residents to major transit hubs, employment centers, anchor institutions, cultural amenities, and recreational opportunities by connecting park space, residential neighborhoods, and the downtown core. This investment in active transportation connectivity should then be connected to existing and planned regional trail assets to better connect the metro area—including the BWI Airport Loop Trail, the Baltimore & Annapolis Trail, the Torrey C. Brown Trail, and the Patapsco Regional Greenway.

With 436 miles of trails in the Washington metro area, the proposed Capital Trails Network would add more than 300 miles of trails, including a connected 45-mile circumferential trail.3 If completed as proposed, millions of residents would live within two miles of a trail, connecting households to jobs, metro stations and regional activity centers.4 The Capital Trails Coalition has identified the 40 most critical trail projects to advance the network.5

The Richmond metro area has two of the oldest national bike routes (U.S. Bike Route 1 and 76) passing through,6 and more than 40 miles of paved trails.7 The Virginia Capital Trail, completed in 2015, connects Richmond to Jamestown, the former capital.

Benefits

Investing in trail networks can change the way the Capital Region’s consumers work, live, and play—in ways similar to the Atlanta BeltLine Trail or the Indianapolis Cultural Trail. The BeltLine plans for 33 miles of multi-use trail (which includes a 22-mile circumferential loop with transit) and will provide bike and walk connections between neighborhoods previously cut off by highway and rail lines.8 As of September 2018, 11 miles of trail are open to the public, including completed permanent segments and temporary interim trails.9 The investment strategy has generated great economic benefit—an 8:1 return on investment, with over $4 billion in private development occurring over the past 10 years, including growth of development during the Great Recession. The investment that has occurred in the Atlanta BeltLine Planning Area is a development benefit for not only the City of Atlanta, but the entire metro region.10

In 2013, Indianapolis completed its eight-mile Cultural Trail, which connects to 40 miles of the existing trail system and six cultural districts spread across the city.11 To complete the $63 million project, Indianapolis leveraged $35.5 million in federal transportation funding and $27.5 million in private funding.12 As a result, the trail has generated an estimated $864.5 million in economic benefits—more than a 13:1 return on investment.13

Active transportation options have also been linked to improving community health outcomes. Research and data modelling conducted by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Nashville metropolitan planning organization (MPO) found that 13 minutes a day of active transportation could reduce rates of 12 chronic diseases.14 By increasing how frequently the average Middle Tennessee resident chose to bike or walk, the Nashville region could save $116 million annually due to reduced direct health treatment costs and gains in productivity.15

Barriers

Each trail corridor is different and offers different challenges. To increase trail usage, barriers to safe and efficient access to the trail entry points by walking, biking, or using transit should be removed. Common barriers faced by other trail projects in the country include competing uses, access to private lands, issues of liability, privacy concerns, local opposition, and funding for planning, construction, and maintenance of the system.

Next moves

The projected benefits from completion of the Baltimore Greenway Trails Network and Capital Trails Network are expected to far exceed costs. Realization of the benefits will not occur until all links of the trail network are connected for these projects, which will require visionary civic leaders; committed elected officials at the federal, state, and local levels; and leadership from private business to deliver success in the near term.

Next moves are:

- Baltimore City, the Baltimore Metropolitan Council (BMC), the Baltimore Greenway Trail Coalition, and the philanthropic community should work with private landowners and neighborhoods to identify timelines and funding sources to complete the Greenway within five years

- The National Park Service, Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (MWCOG), local jurisdictions, and the Capital Trails Coalition should include the Capital Trails Network in the region’s long-range transportation plan and seek funding for priority trail connection projects in annual regional and federal funding grant cycles

- Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Richmond Regional Transportation Planning Organization (RRTPO), and local governments should study and identify a preferred trail route connecting the Virginia Capital Trail in downtown Richmond to points as far north as Ashland with points as far south as Petersburg

Costs

Building regional trail networks requires funding and financing for planning, design, construction, and maintenance. However, building a trail generally costs far less than constructing a mile of additional road lanes. Local and regional governments should prioritize investments in trail networks in their capital programs.

Expand to learn more

Collapse