This is the second post in a three-part series on improving the transit experience in the Washington metro area through enhanced coordination among multiple transit operators. This was a recommendation made in the Greater Washington Partnership’s Blueprint for Regional Mobility, the region’s first CEO-led mobility strategy released in Fall 2018, for the Capital Region, stretching from Baltimore to Richmond.

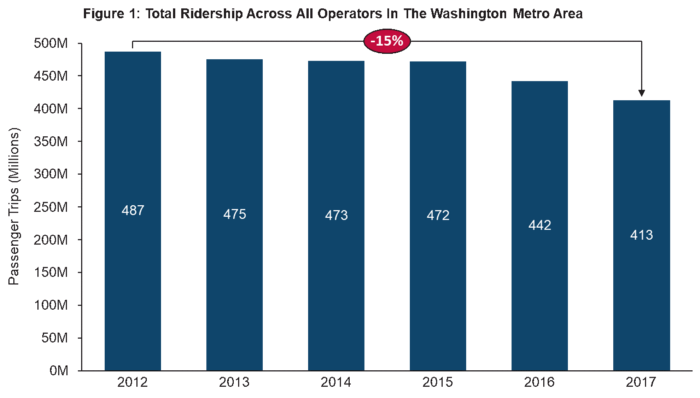

The Washington metro area has extensive and diverse transit options, but fragmentation of its operators and the lack of a central coordinating body diminishes their effectiveness and makes them collectively less competitive, as evidenced by a 15 percent decline in ridership from 2012 to 2017.

Years ago, public transportation in peer regions in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria faced similar challenges. In response, local governments and public transit providers banded together to create regional coordinating associations — Verkehrsverbund (VV) — that integrated all aspects of public transit. These transit networks are far ahead of the Washington metro area — or any other U.S. transit system — in accessibility, ease of use, and level of service. As a result, transit ridership in these peer regions is more than twice that of the Washington metro area.

This blog seeks to introduce how VVs operate, explain the benefits to regional consumers, and raise lessons learned that can be used to inform transit improvements in the Washington metro area.

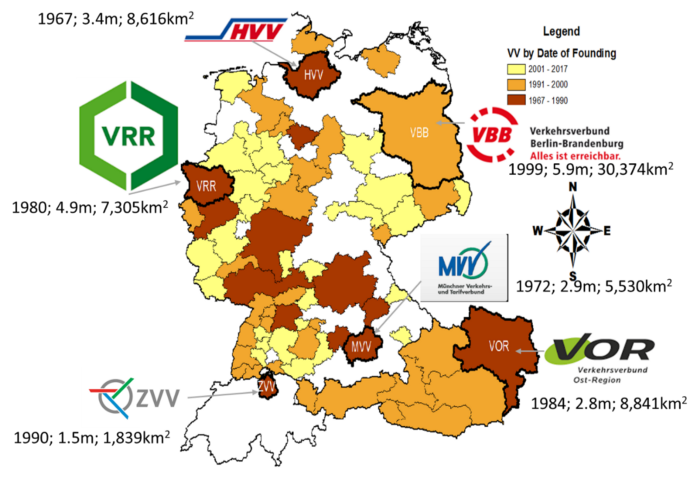

Figure 2: Map of VVs in Germany (63), Switzerland (1), and Austria (7) (highlighted VVs displaying year founded, population, and land area covered)

VV regions have similarities to the Washington metro area. They are located in countries that have federal, state, and local government structures with varying responsibilities for transportation funding and policies. Their regions span multiple jurisdictions and have many transit providers. Not to mention, the first VV was created to counteract steep ridership declines, which is similar to the situation facing the Washington metro area today.

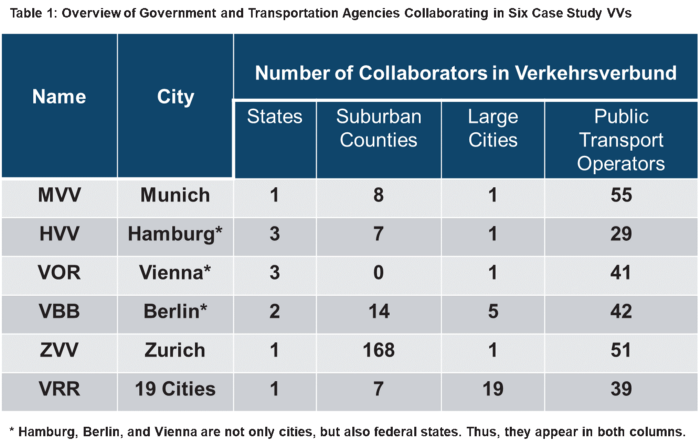

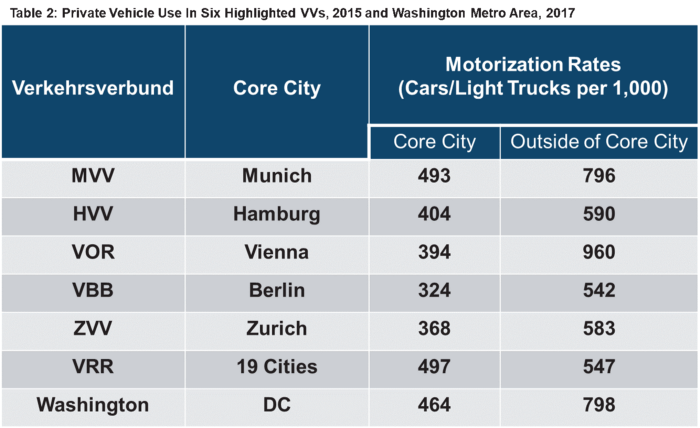

Similar to the Capital Region, many residents in these regions own cars, particularly in suburban areas. As shown in Table 2, car ownership in the Washington metro area is comparable to car ownership in the six highlighted regions.

Source: Analysis completed by authors

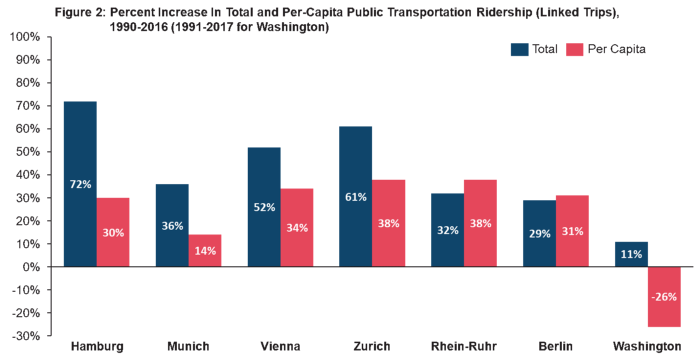

Despite these key similarities, transit ridership in the peer regions is significantly higher than in the Washington metro area. The six VVs had between 168 and 442 transit trips per resident in 2015 — compared to just 48 transit trips per resident in the Washington metro area in 2017. Most of these regions have also experienced dramatic increases in ridership over the past few decades, unlike the Washington metro area. These facts raise an important question: Could the VV model, or something like it, help the Washington metro area reverse years of transit ridership decline?

Source: Analysis completed by authors

VVs Developed in Response to Transportation Challenges Similar to the Washington metro area.

In the 1960s and 1970s, metropolitan areas in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland were facing similar challenges to many U.S. metro areas:

· Car ownership skyrocketed, leading to worsening congestion, pollution, and parking shortages

· The growth of low-density suburbs made it more expensive to provide transit service

· Transit usage fell, posing serious financial problems for transit operators

At the time, regional coordination of public transit was atypical; yet, the central cities viewed improved regional transit as key to reversing their decline, while transit operators sought financial assistance from local governments. Thus, city governments and transit providers had strong incentives to work together.

This situation led to the development of the first VV in 1967. The main transit operator in Hamburg (owned by the city) led coordinating activities in the region to explore ways to facilitate integration of the fragmented services and fares, eventually convincing all transit operators in the region to join in a VV. To address concerns raised by some of the regional transit providers that they would lose revenue by giving up control over fares, the City of Hamburg guaranteed funding to offset losses resulting from integrated operations.

The extraordinary success of Hamburg’s VV in coordinating many disparate transit services was an important factor in encouraging the spread of VVs to other metropolitan areas seeking solutions to declining transit ridership and increasing traffic congestion.

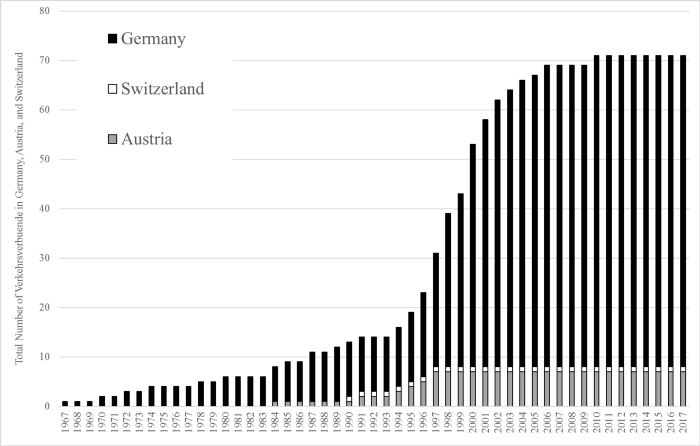

Figure 3: Expansion of VVs in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, 1967–2017

Note: The graph only includes VVs currently in operation, thus excluding VVs that no longer exist because of their amalgamation into larger VVs.

VVs Are Structured to Deliver Regionally Integrated Transit Service.

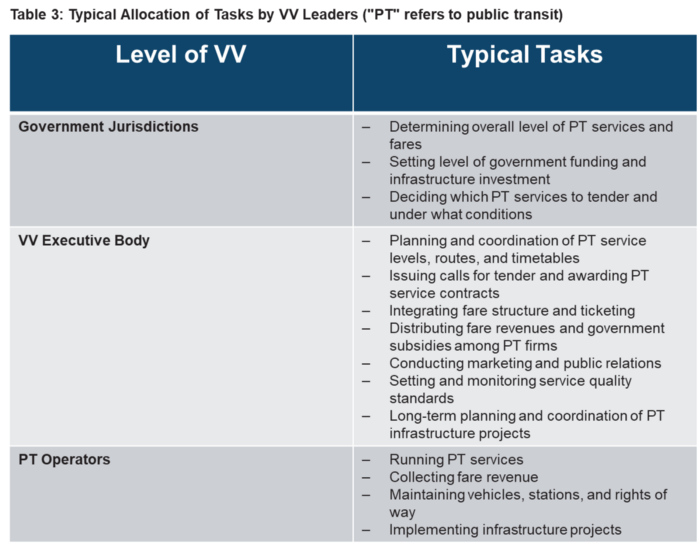

A key feature of VVs is that while specific details of their operations vary, they all share the goal of providing fully integrated transit services, one fare structure, and uniform ticketing throughout their service area. Most VVs are governed by an executive body made up of representatives from jurisdictions and/or public transit operators with the responsibility for planning routes and schedules, integrating fares and ticketing, distributing fare revenues and public funding among transit providers, setting and monitoring performance standards, and disseminating customer information and marketing. Though many VVs began with transit providers playing a leading role, changes to German law in the 1990s gave state and local governments more authority over transportation planning. Today, in most VVs in large metro areas, government jurisdictions have the leading role, but transit providers give important input relating to operations. Table 3 shows the approximate allocation of functions among government jurisdictions, the VV executive body, and transit providers.

There is mutual feedback among transit operators, government jurisdictions, and the VV executive body. For example, government jurisdictions establish the overall level of transit service, but the VV translates that into specific service levels by mode, route, and schedule — with crucial input from the transit operators actually providing the service. Similarly, government jurisdictions jointly determine overall subsidy and fare levels, but the VV translates them into a specific fare structure, and transit operators collect those fares. Government jurisdictions determine which services to contract out, but the VV issues the tenders and awards contracts, and transit operators (both within and outside the VV) compete to provide such services.

VVs Have Made Transit More Competitive.

Although there is variation among VVs in organizational structure and decision-making process, all VVs offer their customers fully integrated regional public transportation. VVs offer one unified route network (all modes, all lines), fully coordinated schedules, and one fare structure and ticketing system. A transit rider in these regions needs to consult only a single transit map to plan a trip. Just one transit pass is needed to complete that trip, regardless of how many different services are used.

This stands in sharp contrast to the situation that existed prior to VVs. In Hamburg, for example, a transit rider needed seven different tickets to cross the city. The enhanced quality of service VVs provide is crucial for transit to compete effectively with the private car, and it seems to be working. VVs in the six highlighted German, Swiss, and Austrian metro areas showed significant increases in total and per-capita ridership between 1990 and 2015.

More Accessible

One reason for increasing transit ridership is more transit service. Indeed, all of the VVs studied, except in Berlin, increased the amount of transit service provided between 1990 and 2015. New and expanded bus and rail routes have brought transit stops closer to more people, providing greater connectivity and more travel options. In most of the VVs, bus and rail services have become more frequent, often in regular, easy-to-remember intervals such as every 10, 15, or 20 minutes. In addition, all of the VVs have modernized buses and rail vehicles and have invested heavily in infrastructure improvements, such as upgraded stations.

Faster

VVs design route schedules to minimize transfer times between different modes and operators. Schedule planning focuses on the entire trip, from origin to destination, with the goal of minimizing both total travel time and problematic transfers across different modes of transit. Waiting times for transfers are among the most frustrating aspects of the transit trip for customers, but synchronization of schedules and stop locations have reduced waiting times for riders, even when transferring between transit modes.

More Convenient

VVs have fully integrated real-time information systems regionwide, both online and on digital displays at station stops and on transit vehicles. Online trip planners suggest the best options, considering all available modes and routes, regardless of transit operator. Integrated information makes it easier for passengers to use transit to go anywhere within the VV’s service area.

Not only are transit services better coordinated, but there is also better coordination of transit with other types of transportation. Bike-sharing and car-sharing agencies are increasingly working together with VVs to offer special monthly or annual tickets that include membership in their programs.

More Affordable

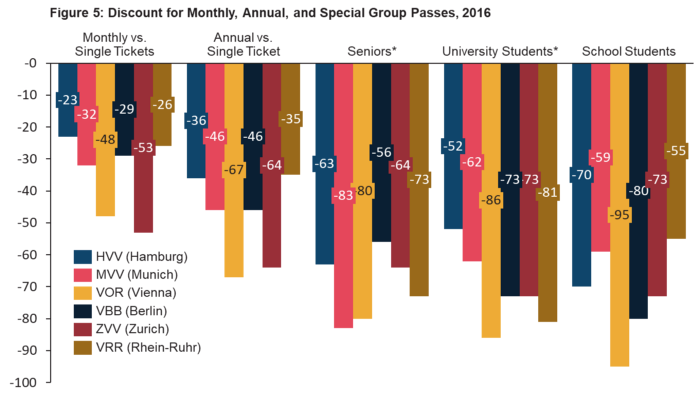

VVs have greatly improved the convenience of ticketing while providing large discounts for regular riders. Single pass programs allow riders to pay once, at the beginning of a month or year (similar to the way car owners pay), rather than paying by the trip. All VVs offer substantial discounts from the regular one-way ticket price for monthly and annual tickets and tickets for special groups. Figure 5 shows the deep discounts riders can receive compared to purchasing 10 regular one-way tickets (i.e., two trips per weekday).

VVs Are Part of an Ecosystem that Prioritizes Transit.

Residents of VV regions benefit from one-stop shopping when it comes to public transit, which undoubtedly accounts for at least some of the ridership increases these regions have experienced. Other factors, separate from VVs, also play a role. While transit fares have increased in all of the case study VVs since 1990, gasoline prices have risen faster, making transit cheaper than driving a car. Cities have limited parking and decreased speeds in downtown areas, further disincentivizing driving.

The result is a transportation system in which transit is competitive with the private car. In 2016, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland had among the highest car ownership rates in Europe. But, those high rates did not deter their residents from making almost half of their daily trips by walking, cycling, and using public transit. By comparison, in the U.S., walking, cycling, and using public transit together accounted for only 14 percent of all daily trips in 2017.

Increasing the use of alternatives to driving is a stated goal of the Washington metro area’s transportation and planning agencies. The VV model has helped many cities in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland achieve that very same goal. In our next post, we will consider how the experience of these international regions may be relevant to solving transportation challenges in the Washington area.

Coauthored with Sarah Kline, and Ralph Buehler