This is the first post in a three-part series that unpacks the Blueprint for Regional Mobility recommendation encouraging the region to enhance coordination of transit planning and operations in the Washington metro area to provide superior consumer experience and better compete for trips. The Blueprint for Regional Mobility, the region’s first CEO-led mobility strategy, was released in Fall 2018 by the Greater Washington Partnership.

The Capital Region, which extends from Baltimore to Richmond, has a diverse mix of transit assets that provide nearly 1.8 million trips on an average weekday. The Washington metro area has the most extensive variety of transit services in the region — a feature that should set this area apart from most of its peers when it comes to mobility. But its fragmented, poorly coordinated transit services make the system less convenient, less dependable, and less competitive than it should be.

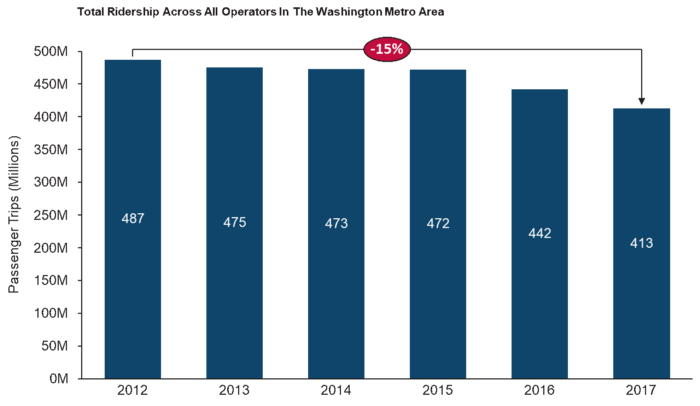

The Washington metro area’s 6 million residents and more than 22 million annual tourists are increasingly using private cars or rideshares, rather than transit, to get around. From 2012 to 2017, transit ridership across all operators in the metro area, including both bus and rail, declined by 15 percent. Some of those declines are in response to the Metro’s multi-year Back2Good maintenance program, which decreases ridership in the short term as riders choose other options to avoid closures and other service disruptions. But Back2Good cannot explain the whole decline: riders aren’t returning to the rails at pre-construction rates once construction periods end, and bus ridership is continuing to fall.

Statistics show that the Capital Region has a regional workforce:

- Nearly 50 percent of commuters in the region wake up in one county and work in another.

- Nearly 20 percent cross state borders to get to their jobs.

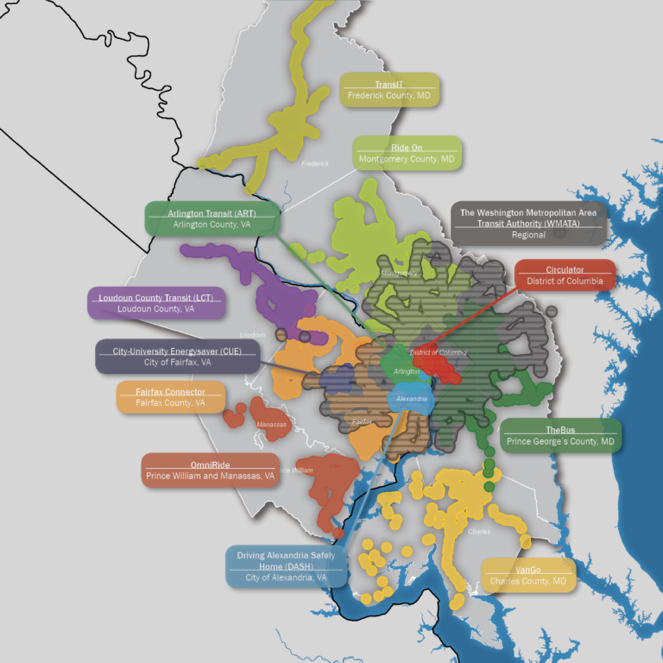

Yet, transit operations across the Washington metro area are fragmented and don’t adequately match the region’s transport demands. The Washington area has 15 bus providers, two commuter rail operators, a regional subway system, streetcar service, commuter buses, paratransit, and a soon-to-be-delivered independent light rail service. While the transit options are numerous, navigating these services can be a major challenge for the region’s residents, and, in some instances, discourage their use. For example, to travel from Maryland to Virginia for work, as thousands do every day, riders may have to start on a local bus (like Ride-On), switch to Metrorail, then end the trip on another local bus (like Fairfax Connector). Traversing these separate services requires riders to confront a challenging array of fares, apps, and schedules to complete a single trip.

The Washington area’s transit operators are missing an essential ingredient: consistent, committed multi-jurisdictional coordination to make transit the easiest, fastest, and most reliable transportation option for its residents. If these services were better coordinated, they could be significantly more competitive and offer a better consumer experience, limit roadway congestion, enhance access to opportunity for all wage earners, and serve as a key attractor for talent and employers.

In this blog series, we will explore the question: Why is the Washington metro area’s transit system so fragmented and what can be done about it? This first post examines the current state of coordination with regard to customer-facing elements of transit, such as trip planning, payment, and fares.

Map Of Bus Providers And Their Service Areas In The Washington Metro Area

Trip planning across operators remains challenging for some.

The first challenge faced by residents and visitors using transit in the Washington area is planning their trips across the various transit operators. To use transit, consumers must not only be aware that transit is an option, but also know how to plan and pay for their trip. A bad or cumbersome experience can and will deter potential riders before they even step on the bus or train. Regular commuters who establish familiar patterns are less susceptible to minor inconveniences, but for a family with children trying to take transit to Nationals Park for a game, or an older resident who needs to get to Washington Hospital Center for a doctor’s appointment, the process of planning and paying for multiple transit systems can be daunting, leading potential riders to choose other options (such as cars).

Some tools have been developed to ease rider confusion. For example, transit trip planning in the Washington metro area can be accomplished through WMATA’s online Trip Planner or various third-party apps. The plethora of planning tools is a relatively new phenomenon. It took five years, from 1999 to 2004, for the Trip Planner to include all transit services in the metro area. Google Maps followed (but only after Google negotiated separately with each provider for their individual transit service feeds). Other privately-developed apps, such as the Transit app, also combine information from multiple transit providers into a common interface.

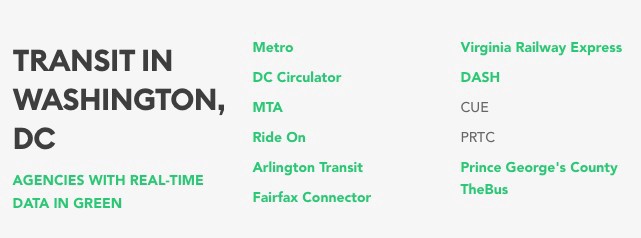

In the early 2000s, technology advanced to allow transit operators to provide users with real-time bus and train status information. Transit providers in the Washington area responded, not by launching an area-wide, real-time information system, but by separately launching their own real-time notification services. Private developers have created apps that combine real-time information from many, but not all, transit providers in the metro area. This makes it difficult for riders who use multiple transit services to easily find real-time information in one place or identify the right app to use.

The privately-developed Transit app covers most, but not all, Washington area transit operators.

Source: https://transitapp.com/region/washington-dc, accessed on May 9, 2019

Fares aren’t fair.

A second challenge is that assessing the cost of a transit trip is a messy transaction. Costs depend on the time of day, transfer policies between services, and whether riders have discounted or free passes that are accepted across the system. The Washington area’s transit operators offer various discounts for specific populations, determined separately by each provider. None offer discounted fares for lower-income residents. Disparities between bus and rail fares and transfer policies may even lead some individuals to take longer, less-efficient trips to save money. For example, an individual may take the 96 bus from Benning Road Station to a job in Tenleytown rather than rail, saving as much as $2.20 per trip during peak hours but paying in wasted time, nearly doubling the length of his or her commute.

Some of the inequities in current fare policies could be addressed with affordable weekly or monthly passes that can be used across multiple systems, which could ultimately increase ridership and reduce riders’ cost per trip, as found in Metro’s Stabilizing and Growing Ridership report. This approach would stand in stark contrast to the manner in which passes are currently offered. Today, purchasing a Metro SelectPass or CommuterConnections pass requires a challenging registration process, route planning, and research far different from the simple process for creating an Uber or Lyft account. Neither pass can be paid for or managed through a smartphone app, and there is no universal pass for all transit options in the region.

Paying for a trip is (mostly) coordinated, but major changes are on the horizon.

Paying for their trips is yet another hurdle riders face when using multiple transit services. Metro was a trailblazer in 1999 when it launched SmarTrip, the nation’s first contactless transit farecard. By 2008, nearly ten years later, all of the local bus systems had completed the farebox upgrades needed to accept the new card. However, uniform adoption of SmarTrip throughout the metro area remains elusive, with MARC and VRE unable to accept this payment option. While consumers can add funds to their SmarTrip cards online, the physical card (or cash) is still required to pay for nearly all transit trips.

The good news is that the Washington area’s transit providers are now developing plans to accept mobile payments, where riders would need only their smartphone. A coordinated areawide approach to mobile payment would benefit transit riders, who could quickly and easily pay for trips regardless of provider. The bad news: Early signals suggest areawide coordination has so far been limited. Metro’s announcement that its mobile platform would be ready by the end of 2019 caught many — even other transit providers, who had been planning their own mobile applications — by surprise. If the lack of coordination means that integrated and seamless mobile payments will take years to be accepted throughout the Washington area’s transit network, transit riders will continue to turn to more convenient options such as ridesharing.

Bus Rapid Transit offers a prime opportunity for coordination and ridership growth.

Another looming challenge is the lack of coordination around the Washington metro area’s new investments in Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) lines. To make transit a more competitive choice for more residents, at least five agencies are studying, planning, or implementing BRT systems, yet there has been minimal coordination between jurisdictions. Metroway in Arlington and Alexandria and Montgomery County’s Flash service along U.S. 29 — the first two BRT lines in the Washington metro area — have been given different brands, with a third brand possible for the BRT line being constructed on Richmond Highway. A consistent brand was a high priority for Metrorail’s architects in creating the subway system. We can only imagine what “America’s subway” would look like today if each line had been designed separately, without standard platforms, signage, fare machines, etc. Yet, that is the process being followed for BRT.

After the Purple and Silver Lines, these BRT routes are the most significant capital investments the metro area is making in transit. Designing and marketing them separately will create an even more confusing landscape for riders, adding yet another set of fares, tickets, and apps into the mix. Moreover, if decisions about dedicated lanes and signal priority are not coordinated across jurisdictional lines, riders are likely to find that their quick BRT trip through one jurisdiction slows to a crawl in the next, reducing performance, increasing operating costs, and lowering ridership for the entire network.

No one entity is accountable for delivering a unified, seamless, consumer-oriented regional transit network.

No single entity is responsible for creating an easy to navigate, user-friendly, consumer-oriented transit system. Each transit operator does its best to improve the consumer’s experience on its own service, but no one entity or organization has this responsibility for the entire Washington area. Even entities with a more regional scope have limited ability to coordinate services.

· The Transportation Planning Board’s Regional Public Transportation Subcommittee conducts studies, such as this assessment of how bus services could be better coordinated, and facilitates information sharing among transit providers.

· The Northern Virginia Transportation Commission (NVTC) is a forum for discussion among Northern Virginia transit providers, and also assists with planning cross-jurisdictional projects.

· WMATA often serves as the convener of technical working groups, and is now spearheading a broad effort to better understand how Metrobus should fit into the metro area’s transit network.

But these individual efforts have not led to better service, and unless an entity emerges to strategically and proactively deliver areawide solutions, operators will continue to experience ridership declines.

As shown in this blog, transit coordination in the Washington metro area is often piecemeal — focused on narrow issues or projects, with slow and variable levels of adoption. The metro area lacks a shared aspiration and commitment to making its collective public transit network the best and most convenient option for a greater share of trips, nor does it have the mechanisms in place to deliver such a vision. Though many in the Washington area would agree that a seamless transit network is desirable, no entity has been formally tasked with delivering that network. As a result, transit has become the last choice for many people in the metro area, when it could and should be the first.

Complex as the Capital Region is, we are not unique in the challenges we face. The next two posts, in a three-part series, will explore leading examples of regional transit coordination from European regions and look at recommendations for enhanced transit coordination in the Washington metro area.

Coauthored with Sarah Kline, and Ralph Buehler